|

Originally posted at The Hooded Utilitarian. A few months ago, Sophie Campbell posted an update to her blog about her ongoing comic series, Wet Moon. After reassuring readers that she was making progress on the seventh installment, she shared the news that volume eight will likely be the last. “I’ll be calling it quits after that, at least for a while,” she writes. And though she hints at the possibility of some kind of spin-off, Campbell seems pretty clear about her need for creative breathing room away from Wet Moon, and perhaps even some closure. Her remarks are what prompted my question this week: when and under what circumstances should a comic series end?

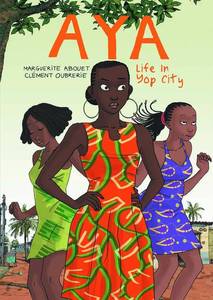

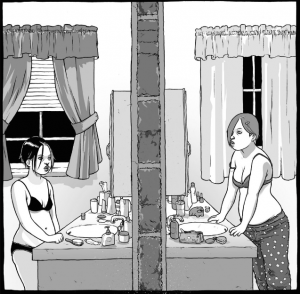

Oni Press first began publishing Campbell’s series in 2005, so as she mentions in her post, it’s been nearly a decade since Cleo, Trilby, Audrey, and Mara started their first year at the art school in their hometown of Wet Moon, somewhere in the Deep South. The comic’s young aspiring poets, playwrights, and illustrators are chain-smoking goths and metal heads, young vegan swamp things who hang out in coffee shops and indie video stores between classes. Not surprisingly, a sense of panic, self-questioning, and irrepressible curiosity underscores their transition from high school to college. Even more interesting, though, is how Campbell’s narrative and aesthetic style values intersectionality in ways that the characters themselves are still struggling to appreciate. In the generous curves and angles of their bodies, gender, race, sexuality, ability, and regional identities are alternatively extolled and effaced according to the shifting cultural attitudes and language of youth. Elements of horror and mystery add even more energy to comic’s coming-of-age drama.  Originally posted at Fledgling: Zetta Elliot's Blog. It is unlikely that anyone who reads comics regularly will be surprised by Zetta Elliott’s answer to the question posed in her January 6, 2014 post, “Do Comics Empower Black Girls?” She’s doubtful, and understandably so, given the hypersexualized objectification of women that dominates superhero comics. Nevertheless, comics can tell deeply rewarding, complex stories about black women that affirm their intelligence, compassion, strength, and beauty on multiple visual and verbal registers. So I come away from the question with a different response, not only as someone who studies race and comics, but also as a black girl who has found much to love in a comic book. Let’s be clear, though, about the term “comics.” Critics often take issue with the depiction of women in superhero titles produced by Marvel (Disney) or DC Comics (Time Warner), but it’s a mistake to equate the superhero genre and its transmedia properties with the entire comics form. This isn’t to say that mainstream superhero comics completely ignore the lives of women of color or refuse to engage contentious social issues. Storm is one of the most well known heroines of any race to wear a cape and a Wakandan princess has held the title of Black Panther. The new Ms. Marvel is Kamala Khan, a Muslim Pakistani-American teenager from New Jersey. Yet one need only look back at Don McGregor’s account of his exchange with Stan Lee over Marvel’s first interracial kiss – or more recently, “Batwomangate” – to get a sense of the effort required to take even small, measured risks in a mainstream superhero comic. But what about fantasy, romance, horror, slice-of-life, and adventure stories? What about small and independent presses or self-published titles? What about comics produced outside the United States? Originally posted at Pencil Panel Page.

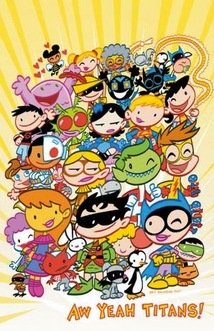

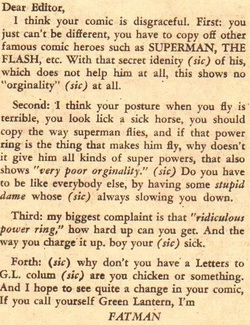

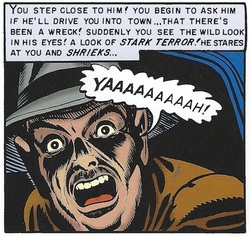

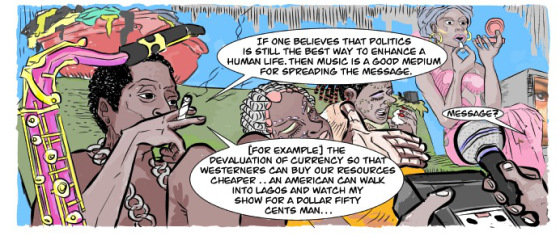

The answer to this post’s title is both, of course. But I’ve posted the question in order to think about the different kinds of reading (and viewing) experiences that comics generate and why we value certain storytelling modes over others. Thanks to an article in Colorlines, I recently discovered 3bute, a transnational online comics “mashable anthology” that describes its goal as “adding visuals and crowdsourced context to African literature and journalism on the web.” Artist Bunmi Oloruntoba and editor Emmanuel Iduma collaborate with reporters and creative writers to furnish “the contexts often missing when African stories are reported.” Every two weeks, 3bute [pronounced "tribute"] publishes a three-page comic from a different African country in which readers tag the images like a wiki page with links to videos, articles, slide shows, twitter posts, music tracks, and other media. The resulting comic is dotted with icons that appear as you touch or move your mouse over its surface. The interactive features blink and pop as you shift from panel to panel in the site’s effort to undermine “the single, one-dimensional story of poverty, sickness, conflict” that far too often disparages the continent. 3bute uses new technology to explore the contours of African modernity through “multifaceted stories,” arguably drawing upon the collaborative traditions that are reminiscent of the open-ended serial narratives from the early-twentieth century – Bud Fisher’s Mutt and Jeff or The Gumpsby Sidney Smith, for instance – newspaper strips that welcomed audience interaction with the world of the characters.  Originally posted at Pencil Panel Page. My daughter started first grade last month and we are reading constantly – anything with words – street signs, food labels, chapter books, and of course, comics. She prefers comic books based on her favorite TV shows (SpongeBob SquarePants, Disney Fairies) along with a few that I enjoy myself, like Art Baltazar’s Tiny Titans… aw yeah, Titans! I have found, though, that reading these stories aloud to her can be an unexpectedly awkward experience, one that may be useful for our conversations here at PPP. It’s hardly as straightforward and immersive as reading a novel and lacks the familiar rhythms of story hour at the public library, in which one recites the words in a picture book before pausing to display the accompanying images. Instead you are compelled to provide your own attribution for the dialogue in a comic, taking care to describe visual components and abstract inferences along with any necessary exposition. You have to note the placement of narrative boxes, sounds, and characters before determining the order in which to convey the events taking place. And if you’re reading to someone fairly new to comics like my six year old, whose eyes roam wildly around the colorful pages, you may end up having to point out key elements in each panel. If you approach the comic as if it is Goodnight Moon, you will be left stumbling. The demands placed on both the reader and the listener (or viewer) are substantial.  Originally posted at Pencil Panel Page. Serial comic books seldom end with a letters column these days, but I’ve begun to appreciate the notes from readers more and more in my research. I never imagined that I would be planning a trip to the Library of Congress to read 1950s comics that are readily available in reprints, merely so that I can browse the original fan letters as well as the ads and other promotional material in circulation at the time. So my question this week is pretty simple: what is the value of the letters column to you? Of course, letter pages from the 1950s, 60s, and 70s were hardly straight-forward monologues of fan response. The columns are well known for staging conversations between readers and comic book creators in ways that I have always found fascinating. The replies from the editors are often carefully crafted teasers for upcoming issues or tongue-in-cheek rebuttals to criticism; witness the way in which the Green Lantern editor responds to the above letter by ridiculing the reader’s spelling errors! Even the most selective, highly-mediated exchanges can offer some insight into the brambles of reader response and the creative process.  Originally posted at Pencil Panel Page. The skin-crawling sense of unease that EC Comics artists and writers once gleefully instilled in their readership during the 1940s and 1950s often begins with a disorienting second-person present perspective. In Al Feldstein’s 1951 story “Reflection of Death”from Tales from the Crypt #23, “you” are a middle-aged white man named Al on a long road trip with a friend who drives late into the winter night. After your car veers into a set of oncoming headlights and crashes, you see through Al’s eyes as he emerges from an “empty” and “eternal” blackness in search of assistance. The men and women you encounter (even a hobo cooking stew under a bridge!) refuse to help and flee from you with mounting fear and revulsion until at last, when you behold yourself in a mirror — a dead, rotting reflection gapes back. If this is a nightmare, then you are its monster. My understanding of this technique has always been grounded in the formalist discourse of reader identification. But are the social implications of EC’s second-person perspective worth further consideration? The second-person mode, so effectively deployed in suspense, horror, and erotica stories, heightens our ability to identify with the thoughts and sensations of bodies that are unfamiliar to us, to immerse ourselves in lives we may never encounter on our own. (A chilling thought for readers who are asked to imagine themselves as a walking corpse.) This unwitting urge to empathize with the Other is arguably the most crucial component of the second-person view, particularly given its role in EC’s most memorable stories. The issue extends not only to comics in which the perspective is verbally explicit, but also to works like “Judgment Day” and“Master Race” where a second-person mode dominates the visual orientation of the sequential narrative. |

AboutAn archive of my online writing on comics, literature, and culture. (Illustration above by Seth!) Categories

All

Archives

July 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed