|

Originally posted at Pencil Panel Page.

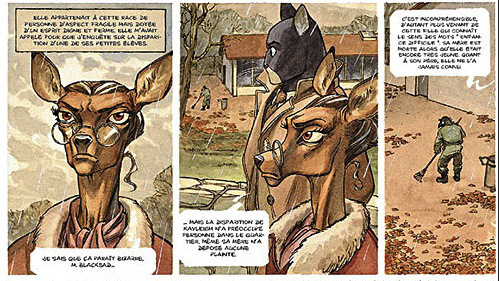

The Silver Age is often defined by the ways in which comic book superheroes began to develop into increasingly complex figures who managed to right great wrongs in spite of their deep insecurities, imperfections, and strange idiosyncrasies. Some readers characterize them as anti-heroes with ambivalent souls and feet made of clay; others simply describe them as “more human.” Proudly eschewing idealized notions of heroism in the 1960s, Marvel championed the foibles of the Amazing Spider-Man: “the superhero would could be – you!” But talking animals have long occupied the “more human” spaces on the comics page and the question I’d like to pose this week is part of my effort to understand their appeal. Despite the industry’s unshakable association with “funny animal comics” (we have titles like the wildly popular Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories to thank for that), anthropomorphic creatures follow a long tradition of embodying our desires and aspirations whether they originate from myths, folk tales, or children’s cartoons. What’s fascinating to me is the figurative pliancy of animal representations, especially when it comes to heightening the reader’s identification with the characters. As comics readers move from Herriman’s Krazy Kat to Kelly’s Pogo to Crumb’s Fritz the Cat to Speigelman’s Maus, the notion that what we encounter are animals made to act like humans is utterly eclipsed by the troubling realization that these creatures are little more than people who act like “animals.” Pogo put it best: “Yep son, we have met the enemy and he is us.” |

AboutAn archive of my online writing on comics, literature, and culture. (Illustration above by Seth!) Categories

All

Archives

July 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed