|

Originally posted at The Hooded Utilitarian. A few months ago, Sophie Campbell posted an update to her blog about her ongoing comic series, Wet Moon. After reassuring readers that she was making progress on the seventh installment, she shared the news that volume eight will likely be the last. “I’ll be calling it quits after that, at least for a while,” she writes. And though she hints at the possibility of some kind of spin-off, Campbell seems pretty clear about her need for creative breathing room away from Wet Moon, and perhaps even some closure. Her remarks are what prompted my question this week: when and under what circumstances should a comic series end?

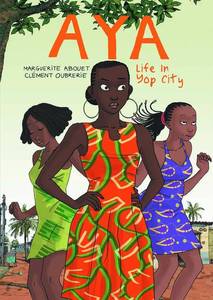

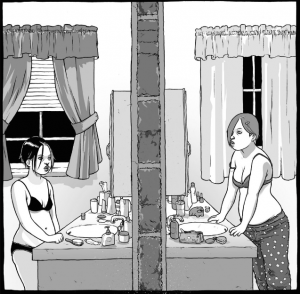

Oni Press first began publishing Campbell’s series in 2005, so as she mentions in her post, it’s been nearly a decade since Cleo, Trilby, Audrey, and Mara started their first year at the art school in their hometown of Wet Moon, somewhere in the Deep South. The comic’s young aspiring poets, playwrights, and illustrators are chain-smoking goths and metal heads, young vegan swamp things who hang out in coffee shops and indie video stores between classes. Not surprisingly, a sense of panic, self-questioning, and irrepressible curiosity underscores their transition from high school to college. Even more interesting, though, is how Campbell’s narrative and aesthetic style values intersectionality in ways that the characters themselves are still struggling to appreciate. In the generous curves and angles of their bodies, gender, race, sexuality, ability, and regional identities are alternatively extolled and effaced according to the shifting cultural attitudes and language of youth. Elements of horror and mystery add even more energy to comic’s coming-of-age drama.  Originally posted at Fledgling: Zetta Elliot's Blog. It is unlikely that anyone who reads comics regularly will be surprised by Zetta Elliott’s answer to the question posed in her January 6, 2014 post, “Do Comics Empower Black Girls?” She’s doubtful, and understandably so, given the hypersexualized objectification of women that dominates superhero comics. Nevertheless, comics can tell deeply rewarding, complex stories about black women that affirm their intelligence, compassion, strength, and beauty on multiple visual and verbal registers. So I come away from the question with a different response, not only as someone who studies race and comics, but also as a black girl who has found much to love in a comic book. Let’s be clear, though, about the term “comics.” Critics often take issue with the depiction of women in superhero titles produced by Marvel (Disney) or DC Comics (Time Warner), but it’s a mistake to equate the superhero genre and its transmedia properties with the entire comics form. This isn’t to say that mainstream superhero comics completely ignore the lives of women of color or refuse to engage contentious social issues. Storm is one of the most well known heroines of any race to wear a cape and a Wakandan princess has held the title of Black Panther. The new Ms. Marvel is Kamala Khan, a Muslim Pakistani-American teenager from New Jersey. Yet one need only look back at Don McGregor’s account of his exchange with Stan Lee over Marvel’s first interracial kiss – or more recently, “Batwomangate” – to get a sense of the effort required to take even small, measured risks in a mainstream superhero comic. But what about fantasy, romance, horror, slice-of-life, and adventure stories? What about small and independent presses or self-published titles? What about comics produced outside the United States? |

AboutAn archive of my online writing on comics, literature, and culture. (Illustration above by Seth!) Categories

All

Archives

July 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed