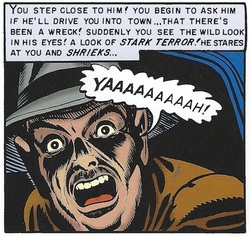

Originally posted at Pencil Panel Page. The skin-crawling sense of unease that EC Comics artists and writers once gleefully instilled in their readership during the 1940s and 1950s often begins with a disorienting second-person present perspective. In Al Feldstein’s 1951 story “Reflection of Death”from Tales from the Crypt #23, “you” are a middle-aged white man named Al on a long road trip with a friend who drives late into the winter night. After your car veers into a set of oncoming headlights and crashes, you see through Al’s eyes as he emerges from an “empty” and “eternal” blackness in search of assistance. The men and women you encounter (even a hobo cooking stew under a bridge!) refuse to help and flee from you with mounting fear and revulsion until at last, when you behold yourself in a mirror — a dead, rotting reflection gapes back. If this is a nightmare, then you are its monster. My understanding of this technique has always been grounded in the formalist discourse of reader identification. But are the social implications of EC’s second-person perspective worth further consideration? The second-person mode, so effectively deployed in suspense, horror, and erotica stories, heightens our ability to identify with the thoughts and sensations of bodies that are unfamiliar to us, to immerse ourselves in lives we may never encounter on our own. (A chilling thought for readers who are asked to imagine themselves as a walking corpse.) This unwitting urge to empathize with the Other is arguably the most crucial component of the second-person view, particularly given its role in EC’s most memorable stories. The issue extends not only to comics in which the perspective is verbally explicit, but also to works like “Judgment Day” and“Master Race” where a second-person mode dominates the visual orientation of the sequential narrative. Nevertheless, I cite “Reflection of Death” here to invite speculation about the figurative potential of the second-person surrogate when it comes to social issues. While there are certainly numerous ways to read Al’s subconscious “fall,” his mortal fears, and his contemplation of the long dark road home, I wonder if we might also see this white male character’s breakdown within the context of the systemic effects of racial prejudice in the 1950s. Works of African American literature from this period suggest an analogous model for evaluating the suspense and horror tropes in which “you” exist only through the gaze of onlookers, and the agonizing inability to see yourself as you are (not) seen sends you reeling back again into a nightmarish cycle of trauma. Perhaps Feldstein’s bizarre story engenders both the desperation and the self-loathing that ultimately compels comic book fans to experience the kind of racial marginalization with which readers of Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright, and Ann Petry would be familiar. To be sure, the title character of Ellison’s 1952 novel, Invisible Man, takes pains to distinguish the ghosts of classic literature and popular media from his formulation of “invisibility” as a racial condition. Yet at one point in the prologue, he remarks: You wonder whether you aren’t simply a phantom in other people’s minds. Say, a figure in a nightmare which the sleeper tries with all his strength to destroy. It’s when you feel like this that, out of resentment, you begin to bump people back. And, let me confess, you feel that way most of the time. You ache with the need to convince yourself that you do exist in the real world, that you’re a part of all the sound and anguish, and you strike out with your fists, you curse and you swear to make them recognize you. And, alas, it’s seldom successful. (3-4) Do you think the Crypt Keeper would agree? Comments are closed.

|

AboutAn archive of my online writing on comics, literature, and culture. (Illustration above by Seth!) Categories

All

Archives

July 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed