|

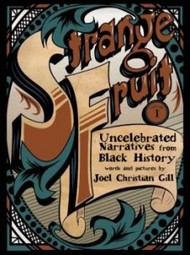

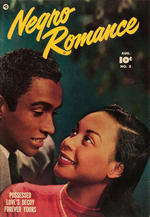

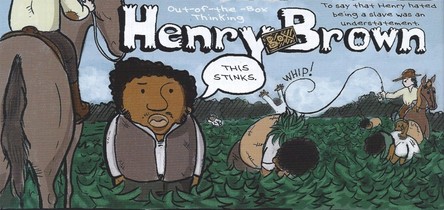

Originally posted at The Hooded Utilitarian.  My copy of Joel Christian Gill’s new graphic novel arrived in the mail last week shortly after I read Frank Bramlett’s post on the way editorial comics depict Michael Sam, the openly gay, black football player who was recently drafted by the NFL’s St. Louis Rams. Of particular interest to Frank was how few of the comics he found rely on metaphor to convey meaning and instead invoke more literal representations of Sam to comment upon the significance (or insignificance) of his social identity. As the post makes clear, scrutinizing the visual and verbal shorthand that comics use to illustrate abstract ideas like race or sexual orientation can reveal a great deal about how society negotiates changing attitudes, institutions, and avenues of power. Gill’s collection, Strange Fruit: Uncelebrated Narrative from Black History, provides us with another opportunity to raise questions about the figurative modes of expression that today’s comics creators use to represent race and racism. Readers of the short stories in Strange Fruit quickly learn to appreciate the playful succinctness of Gill’s iconographic language. He knows when to use humor and sight gags to advance the story. (On the experience of enslavement, Henry “Box” Brown remarks: “This stinks.”) But Gill knows when more serious cultural cues are needed too, as in the two-page spread where Brown’s body, shown curled inside a wooden box, silently tumbles from slavery to freedom.  Originally posted at Pencil Panel Page. I’ve spent the first few weeks of my African American Comics class dispelling myths. With a sharp and tremendously engaged group of diverse university students, we’ve tackled questions not just about the form, but also about the range of black representation in America’s earliest comics from Outcault’s The New Bully and Herriman’s Musical Mose to Dell’s New Funnies, Fawcett’s Negro Romance, and EC’sShock SuspenStories. This week I asked the class what surprised them most about our readings so far and a few voiced their initial skepticism that a course on black comics could have enough material to last a full semester. (One student is particularly pleased that she can argue now about comics with friends whose experiences begin and end with Batman.) So far the Negro Romance story, “Possessed” and the first issue of Rural Home’s Jun-Gal have inspired the liveliest exchange. But what has stuck with me is the conversation surrounding our analysis of a Li’l Eight Ball story from a December 1945 issue of New Funnies. The story is very much in keeping with the slapstick humor of other Walter Lantz characters. A clumsy little boy tries to please his mother in a simple plot that revolves around physical comedy and a serendipitous happy ending. Still, the boy in this story has a large shiny pitch black head, oversized pink lips, and wears white gloves. His plump “mammy” wears an apron and handkerchief around her head as she scolds her son’s well-intentioned antics. Originally posted at Pencil Panel Page.

I am fascinated by Musical Mose, an obscure humor comic strip by George Herriman, better known for his critically-acclaimed series Krazy Kat. Published as Herriman’s first continuing series for New York World in 1902, Mose is a traveling black musician whose recitals go awry when he attempts to impersonate a performer of a different ethnicity. In “No Use These Days, To Try To Break Into Those Exclusive Professions” from March 9, Mose is pummeled by a group of Italian men for posing as an organ grinder (see below), while in another episode, he plays an Irish fiddle beautifully, but is assailed by the Tipperary Guards for singing “The Wearing of the Green.” The series lasted for only three or four strips and I’m grateful that Allan Holtz at the Stripper’s Guide blog has made these scans available online. |

AboutAn archive of my online writing on comics, literature, and culture. (Illustration above by Seth!) Categories

All

Archives

July 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed