|

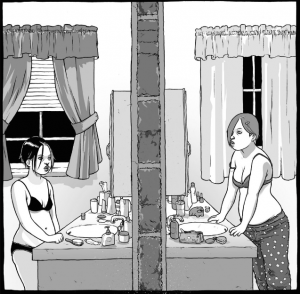

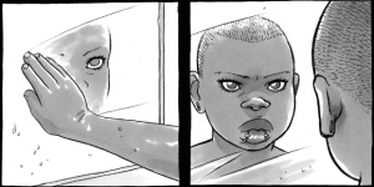

Originally posted at The Hooded Utilitarian. A few months ago, Sophie Campbell posted an update to her blog about her ongoing comic series, Wet Moon. After reassuring readers that she was making progress on the seventh installment, she shared the news that volume eight will likely be the last. “I’ll be calling it quits after that, at least for a while,” she writes. And though she hints at the possibility of some kind of spin-off, Campbell seems pretty clear about her need for creative breathing room away from Wet Moon, and perhaps even some closure. Her remarks are what prompted my question this week: when and under what circumstances should a comic series end? Oni Press first began publishing Campbell’s series in 2005, so as she mentions in her post, it’s been nearly a decade since Cleo, Trilby, Audrey, and Mara started their first year at the art school in their hometown of Wet Moon, somewhere in the Deep South. The comic’s young aspiring poets, playwrights, and illustrators are chain-smoking goths and metal heads, young vegan swamp things who hang out in coffee shops and indie video stores between classes. Not surprisingly, a sense of panic, self-questioning, and irrepressible curiosity underscores their transition from high school to college. Even more interesting, though, is how Campbell’s narrative and aesthetic style values intersectionality in ways that the characters themselves are still struggling to appreciate. In the generous curves and angles of their bodies, gender, race, sexuality, ability, and regional identities are alternatively extolled and effaced according to the shifting cultural attitudes and language of youth. Elements of horror and mystery add even more energy to comic’s coming-of-age drama. Having just read the six volumes of Wet Moon on a weekend binge last year, Cleo and the other characters are new friends of mine. I’m still in the early swoon of fandom and quite satisfied to linger here a while before venturing into more scholarly analysis. But Campbell has lived with the story for ten years or more, and her discomfort with this fact can be instructive for those of us who study comics. Her post concludes: i don’t know if it’ll be career suicide to end Wet Moon, but it seems like the right thing to do. i love the characters but i’ve felt more and more crushed underneath all the storylines i’ve woven together, i feel like i’m paying for the decisions my 24-year-old self made, and i need to wipe the slate clean and move on. other reasons are i feel like i’m always trying to repurpose Wet Moon to fit with myself as i get older and change as a person, people change a lot in 10 years, and also that with each new book, WM gets more and more inaccessible, i don’t want it to become like long-running superhero comics or those Japanese comics that you’re interested in until you find out they’re 25 volumes long and counting. bleh. Campbell’s concerns could easily apply to any form of storytelling with recurring characters, from Sherlock Holmes mysteries to daytime soaps or the prequels and sequels of Star Wars. Yet comics struggle with the pleasures and burdens of serialization in distinctive ways. The form’s most popular genres, such as the long-running superhero comics that Campbell references, are often bound to the creative decisions of the past and to the fans who want to keep it that way. As Danny Fingeroth explains, “We learn and grow – we change – from experience. For the most part, serialized fictional characters do not. This is at once a great strength and a terrific weakness for them.” Clearly the same can be said of their creators too. Campbell cites the complex continuity in Wet Moon and the related issue of inaccessibility, along with her own personal growth as reasons to risk what could be “career suicide.” (Given her recent work on TMNT, the weekly updates to Shadoweyes, and everything else she’s done, I don’t see that happening.) But Wet Moon offers its own evidence of the rewards that can come with taking such a risk. Consider the way Cleo’s friend Mara slowly sheds her brooding intensity over the course of the series along with her nose rings, leather mini-skirts and black lipstick. “Just felt like it,” she says to Audrey in book 3, but Mara’s journal reflects her frustration with a life in which everyone seems to be changing except her: “i took out a lot of my piercings too, it seemed like the right thing to do, i was getting sick of them… sometimes lately i feel like i don’t know who i am anymore. i know that sounds totally lame and emo or whatever, but it’s true and i can’t lie about it.” If being able to see people like Mara learn and grow and change from their experience means that the series won’t last for 25 volumes and counting, then I guess – to borrow a phrase from both Campbell and her serialized fictional character, it does seem like “the right thing to do.” Writer Brian K. Vaughan puts it another way: Most people who love comics, we’re used to things like Spider-Man and Batman, things that have an illusion of a third act. There will never really be a last Spider-Man story or a last Batman story, even though people have tried it. It’ll never really end. And we get spoiled that way. But I think finales are what give stories their meaning. The stories need endings because all of our lives have endings. When I think of a series that ended on a high note, Neil Gaiman’s work on Sandman comes to mind (although he has produced spin-offs and a new mini-series since the mid-1990s), not to mention Vaughan’s own Ex-Machina and Y The Last Man. On the other hand, I think Aaron McGruder’s social and political interests developed as a cartoonist during his time on The Boondocks in ways that did not reflect well on the quality of the strip. And I wonder about a series like The Walking Dead now that the television adaptation has become more well known than the comic. While superhero comics are obviously relevant here too, I’m more interested in creator-owned titles or story arcs created by a single writer and/or artist who is inextricably linked to the series’ identity.

So let’s talk about endings. Which creators or titles get them right? Where are the missed opportunities? We could even consider the larger implications of Campbell’s concerns about the inaccessibility of long-running serials or Vaughan’s suggestion that comics storytelling can sometimes suffer without the sense of finality that endings provide. Comments are closed.

|

AboutAn archive of my online writing on comics, literature, and culture. (Illustration above by Seth!) Categories

All

Archives

July 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed