|

Originally posted at The Hooded Utilitarian.

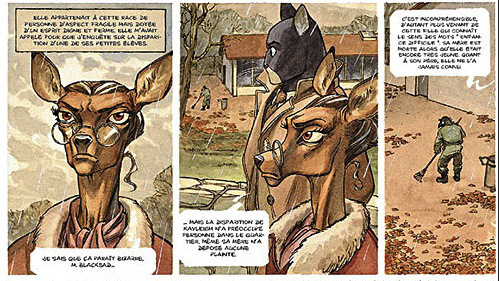

In their essay collection, Thinking about Animals: New Perspectives on Anthropomorphism, editors Lorraine Daston and Gregg Mitman assert that “humans, past and present, hither and yon, think they know how animals think, and they habitually use animals to help them do their own thinking about themselves.” Prompted by the ubiquitous manifestations of anthropomorphism in the arts and sciences, religion and folklore, advertising, and nature documentary filmmaking, the collection’s introduction charts the various psychological, religious, and ethic orientations toward ascribing human behaviors and characteristics to animals and asks: “Has the animal become, like that of the taxidermist’s craft, little more than a human-sculpted object in which the animal’s glass eye merely reflects our own projections?” The question provides us with an opportunity to linger on the cat and mouse game at the center of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat. We might consider what the comic strip’s premise has inherited from Anansi, Aesop, Brer Rabbit, and other tales of talking animals in its serial run from the First World War to the Second, through Women’s Suffrage, the Great Depression, the New Deal, and the Segregation Era. Or we can reflect on how the strengths and weaknesses of Krazy Kat shape our interpretation of animal characters in the comic art and animation that followed Herriman’s lead. Felix, Mickey, Woody, and Fritz come to mind, but anthropomorphic animals as a trope touch a remarkable number of genres and styles, including titles such as Fables, Mouse Guard, Beasts of Burden, Pride of Bagdad, Bayou, Blacksad, and We3. And of course, given the subject of recent conversations on HU, we might even wonder: if it wasn’t for Krazy Kat, would we even have Art Spiegelman’s Maus? Originally posted at Pencil Panel Page.

The Silver Age is often defined by the ways in which comic book superheroes began to develop into increasingly complex figures who managed to right great wrongs in spite of their deep insecurities, imperfections, and strange idiosyncrasies. Some readers characterize them as anti-heroes with ambivalent souls and feet made of clay; others simply describe them as “more human.” Proudly eschewing idealized notions of heroism in the 1960s, Marvel championed the foibles of the Amazing Spider-Man: “the superhero would could be – you!” But talking animals have long occupied the “more human” spaces on the comics page and the question I’d like to pose this week is part of my effort to understand their appeal. Despite the industry’s unshakable association with “funny animal comics” (we have titles like the wildly popular Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories to thank for that), anthropomorphic creatures follow a long tradition of embodying our desires and aspirations whether they originate from myths, folk tales, or children’s cartoons. What’s fascinating to me is the figurative pliancy of animal representations, especially when it comes to heightening the reader’s identification with the characters. As comics readers move from Herriman’s Krazy Kat to Kelly’s Pogo to Crumb’s Fritz the Cat to Speigelman’s Maus, the notion that what we encounter are animals made to act like humans is utterly eclipsed by the troubling realization that these creatures are little more than people who act like “animals.” Pogo put it best: “Yep son, we have met the enemy and he is us.” |

AboutAn archive of my online writing on comics, literature, and culture. (Illustration above by Seth!) Categories

All

Archives

July 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed