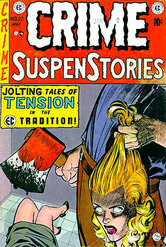

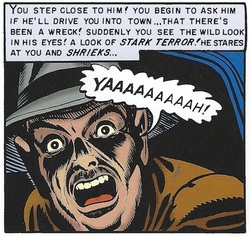

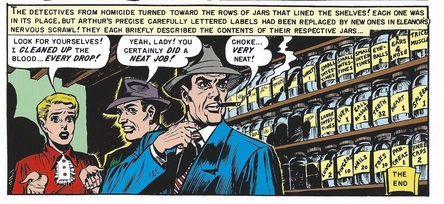

Originally posted at Pencil Panel Page. In the late 1940s and 1950s, the Entertaining Comics Group was well known for resolving conflict through a rather distinctive kind of retributive justice in its horror, suspense, and crime titles. Devious characters who set out to hide their iniquity always seem to fall prey to the elaborate traps that they had designed for others, whether it was inadvertently ingesting their own poison or tripping their own explosives. As EC publisher Bill Gaines explained it, “You broil live lobsters; you end up getting broiled alive… we did have this kind of morality that somebody got back what they gave.” (Which is exactly what happens to the sadistic restaurant owner in “Half-Baked!” from the Feb/Mar 1954 issue of Tales From the Crypt.) I am curious, though, as to what happens when this storytelling strategy intersects with another peculiar and incredibly grim feature of EC’s revenge narratives, that of spousal dismemberment. I’ve been coming across story after story in which men and women, often wronged and abused, end up literally cutting their spouses to pieces. In a crime story called “The Neat Job!” from the Feb/Mar 1952 issue of Shock SuspenStories, for instance, a wife discovers too late that her new husband is a “fiend for neatness” who constantly inspects the way she cleans and organizes, even going so far as to keep checklists of the number of pills in each medicine bottle. When the homicide detectives arrive, the shaken woman points to a wall of jars lined up in the basement, each precisely labeled with parts of her husband’s corpse: Liver 1, Gallbladder 1, Teeth 32, Heart 1… “Yeah, lady!” one detective exclaims, “You certainly did a neat job!”  Originally posted at Pencil Panel Page. The skin-crawling sense of unease that EC Comics artists and writers once gleefully instilled in their readership during the 1940s and 1950s often begins with a disorienting second-person present perspective. In Al Feldstein’s 1951 story “Reflection of Death”from Tales from the Crypt #23, “you” are a middle-aged white man named Al on a long road trip with a friend who drives late into the winter night. After your car veers into a set of oncoming headlights and crashes, you see through Al’s eyes as he emerges from an “empty” and “eternal” blackness in search of assistance. The men and women you encounter (even a hobo cooking stew under a bridge!) refuse to help and flee from you with mounting fear and revulsion until at last, when you behold yourself in a mirror — a dead, rotting reflection gapes back. If this is a nightmare, then you are its monster. My understanding of this technique has always been grounded in the formalist discourse of reader identification. But are the social implications of EC’s second-person perspective worth further consideration? The second-person mode, so effectively deployed in suspense, horror, and erotica stories, heightens our ability to identify with the thoughts and sensations of bodies that are unfamiliar to us, to immerse ourselves in lives we may never encounter on our own. (A chilling thought for readers who are asked to imagine themselves as a walking corpse.) This unwitting urge to empathize with the Other is arguably the most crucial component of the second-person view, particularly given its role in EC’s most memorable stories. The issue extends not only to comics in which the perspective is verbally explicit, but also to works like “Judgment Day” and“Master Race” where a second-person mode dominates the visual orientation of the sequential narrative. |

AboutAn archive of my online writing on comics, literature, and culture. (Illustration above by Seth!) Categories

All

Archives

July 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed