|

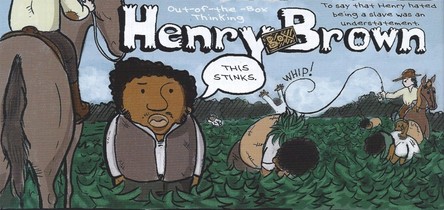

Originally posted at The Hooded Utilitarian.  My copy of Joel Christian Gill’s new graphic novel arrived in the mail last week shortly after I read Frank Bramlett’s post on the way editorial comics depict Michael Sam, the openly gay, black football player who was recently drafted by the NFL’s St. Louis Rams. Of particular interest to Frank was how few of the comics he found rely on metaphor to convey meaning and instead invoke more literal representations of Sam to comment upon the significance (or insignificance) of his social identity. As the post makes clear, scrutinizing the visual and verbal shorthand that comics use to illustrate abstract ideas like race or sexual orientation can reveal a great deal about how society negotiates changing attitudes, institutions, and avenues of power. Gill’s collection, Strange Fruit: Uncelebrated Narrative from Black History, provides us with another opportunity to raise questions about the figurative modes of expression that today’s comics creators use to represent race and racism. Readers of the short stories in Strange Fruit quickly learn to appreciate the playful succinctness of Gill’s iconographic language. He knows when to use humor and sight gags to advance the story. (On the experience of enslavement, Henry “Box” Brown remarks: “This stinks.”) But Gill knows when more serious cultural cues are needed too, as in the two-page spread where Brown’s body, shown curled inside a wooden box, silently tumbles from slavery to freedom. Originally posted at The Hooded Utilitarian.

Early in Jeremy Love’s comic series, Bayou, the murder of a black child named Billy Glass awakens the supernatural southern landscape that surrounds the story’s young female protagonist, Lee Wagstaff. Lee is forced to swim into the bayou to retrieve Billy’s body and afterwards she describes the experience to her white friend, Lily. Stunned by Lee’s description of the bloated corpse, Lily blurts out, “My mama said Billy Glass deserved what he got. She said a n***** boy got no business whistlin’ at no white woman.” In the wordless panel that follows, Lee’s hands drop as a dismayed expression crosses her face. Beside her, Lily’s eyes lower, her shoulders slouch back, and she lets out a small whistle of her own. Readers familiar with the history of the Jim Crow South know that this two-toned whistle once belonged to Emmett Till – the fourteen-year-old boy from Chicago who was killed in Mississippi in 1955 for allegedly whistling at a white woman.* What we hear, then, in Love’s visual rendering of Lily’s whistle interests me greatly, for those tiny eighth notes generate a tremendous sound. We hear echoes of anti-miscegenation panic, a fear that reverberates unease even as the conversation hastily resumes. We hear the sense of white privilege that attends Lily’s ability to whistle freely, carelessly one could argue, in spite of her naïveté as a child repeating her mother’s words. But I believe that what Love also wants us to hear in this sequence is the “wolf whistle” of a murdered black child, along with the memory of just how much that sound costs. Perhaps what resonates most deeply in the white girl’s whistle are the sounds that Billy (and Emmett) are no longer able to make, were never free to make at all.  Originally posted at The Hooded Utilitarian. “You heard her, you ain’t blind.” – Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God In the forward to Phillip R. Ratcliffe’s new biography of Mississippi John Hurt the granddaughter of the country blues guitarist describes what it was like to hear Hurt play for the neighbors in the front yard, sitting in his favorite straw back chair with a warm smile and a pan of roasted peanuts nearby. Again and again, she describes the experience in undeniably transcendent terms and insists that it was his “supernatural spirit that had a far greater effect on people than his music alone” (vii). I wonder what Mary Frances Hurt Wright might think of her grandfather’s cameo appearance in the graphic novel, Stagger Lee — whether or not Shepherd Hendrix’s solemn illustration of the bluesman, or the narrative in which Derek McCulloch enfolds him, can convey the mythical power that she once felt as a listener. The lyrics to “Stackolee Blues” are printed above Hurt’s head in a word balloon edged with eighth notes; a crowd stands nearby. The scene, itself, is part of a larger, deeply fascinating blending of history and legend. But when it comes to conveying the quality of the sound that the crowd hears or the magnetic force Hurt’s granddaughter describes, even the most vivid representation can feel inadequate. It is hard to compare the silence of words and pictures on a page to the sound of that first plucked string. Western artists have been enamored with the figure of the black folk musician in public and private moments going back to the nineteenth century. Modern American poets, most notably Langston Hughes, have aspired to an aesthetic in their verse that exemplifies the blues and the social and economic conditions that brought the music into existence. Nevertheless, blues historian Paul Oliver effectively sums up the challenge that awaits any artist or writer influenced by the sounds of Bessie Smith and Muddy Waters: “Blues is for singing. It is not a form of folk song that stands up particularly well when written down” (8). But can a comic fare any better? Does the form’s interplay of verbal and visual elements provide a more dynamic set of tools for representing blues music and culture? My interest here extends to the distinctive ways in which comics approach auditory signification in particular: how do comics sound? Will Eisner, Scott McCloud and others in comics studies often emphasize comics reading as an active, multisensory encounter, guided not only by what’s on the page, but by what is demanded of the reader’s imagination. Which artistic strategies make for a more satisfying experience when it comes to hearing what we see? |

AboutAn archive of my online writing on comics, literature, and culture. (Illustration above by Seth!) Categories

All

Archives

July 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed