|

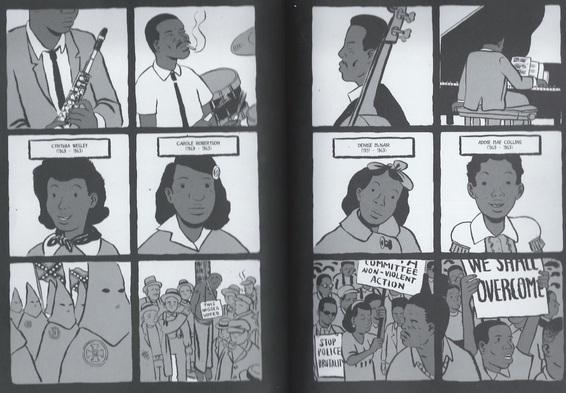

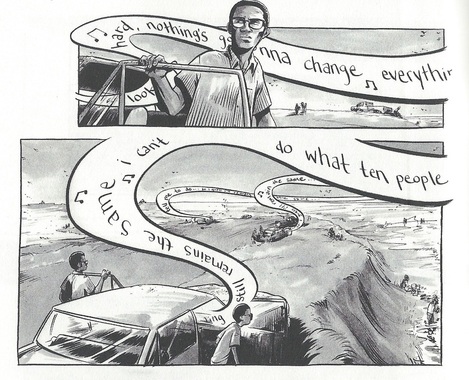

Originally posted at The Hooded Utilitarian. Early in Jeremy Love’s comic series, Bayou, the murder of a black child named Billy Glass awakens the supernatural southern landscape that surrounds the story’s young female protagonist, Lee Wagstaff. Lee is forced to swim into the bayou to retrieve Billy’s body and afterwards she describes the experience to her white friend, Lily. Stunned by Lee’s description of the bloated corpse, Lily blurts out, “My mama said Billy Glass deserved what he got. She said a n***** boy got no business whistlin’ at no white woman.” In the wordless panel that follows, Lee’s hands drop as a dismayed expression crosses her face. Beside her, Lily’s eyes lower, her shoulders slouch back, and she lets out a small whistle of her own. Readers familiar with the history of the Jim Crow South know that this two-toned whistle once belonged to Emmett Till – the fourteen-year-old boy from Chicago who was killed in Mississippi in 1955 for allegedly whistling at a white woman.* What we hear, then, in Love’s visual rendering of Lily’s whistle interests me greatly, for those tiny eighth notes generate a tremendous sound. We hear echoes of anti-miscegenation panic, a fear that reverberates unease even as the conversation hastily resumes. We hear the sense of white privilege that attends Lily’s ability to whistle freely, carelessly one could argue, in spite of her naïveté as a child repeating her mother’s words. But I believe that what Love also wants us to hear in this sequence is the “wolf whistle” of a murdered black child, along with the memory of just how much that sound costs. Perhaps what resonates most deeply in the white girl’s whistle are the sounds that Billy (and Emmett) are no longer able to make, were never free to make at all. Bayou is a blues comic through and through, filled with songs that shake juke joints and others that keep time on a prison chain gang. It may not be all that surprising to find that narrative drawings such as comics draw upon blues, jazz, soul, and other traditionally African American forms to picture racial trauma, given that these genres are already so well known for chronicling social struggle. Still it is worth noting that when it comes to the historical portrayal of racial discrimination and violence in comics, music often serves as a means through which characters process (and repudiate) the senseless and the unspeakable. The brief exchange between Lee and Lily is a powerful reminder that trauma creates its own kind of music in the visual convergence of sound and silence. The interplay generates another compelling moment in Paolo Parisi’s comic biography, Coltrane. (Originally published in Italian, the English translation appears to only be available in the UK.) This scene focuses on the song that the jazz saxophonist created in memory of the 1963 Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, simply titled “Alabama.” The stirring eulogy that Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered for the four girls killed in the bombing may have even inspired the song’s melody. Words transformed through song, now mediated once more through image: I read this two-page grid horizontally in rows of three. The first row acts as prelude with four tight shots of the musicians. Coltrane has not yet lifted the mouthpiece to his lips and the eyes of Elvin Jones, Jimmy Garrison, and McCoy Tyner are hidden or closed in a hush before they begin to play. The second sequence portrays school photographs of the four girls that were murdered. Above their still and smiling faces, the only printed text in each panel is a name and date to remind us how few years Cynthia, Carole, Denise, and Addie Mae lived before that Sunday morning in September. The date stamps cycle around to the year of each girl’s death while above them, it is as if the pictured musicians are keeping a steady beat: 1963. 1963. 1963. 1963. The children’s faces are further juxtaposed against panels that overflow with crowds of people in the third row — the Klansmen with Confederate flags, a photographed lynching, and Civil Rights demonstrators holding signs of protest. Whether or not the reader has actually heard “Alabama,” the soundtrack to the Birmingham church bombing is here on Parisi’s page. Coltrane’s saxophone glides over the piano’s opening rumble and plunges into the percussive crescendo at the close. The scene facilitates an elegy of a different sort through stillness and motion, and in the pacing and symmetry of iconic images from the era. Its composition brings to mind a passage from the collection, Sing for Freedom: The Story of the Civil Rights Movement Through Its Songs: Anyone familiar with the musical characteristics of Negro folk style in spiritual and gospel singing, in blues and rock n’ roll, will know that these transcriptions represent only a bare skeleton of what is actually being sung. Good singers will subtly vary the tune – bending notes, delaying or anticipating the beat, and adding their own vocal decorations. (6) Graphic narratives take an analogous approach with some comics choosing not to venture too far beyond transcription, while others vary, decorate, and bend. Indeed, Bayou and Coltrane are not the only texts that improvise among the sounds of the Jim Crow South. Examples appear throughout The Silence of Our Friends, written by Mark Long and Jim Demonakos, and illustrated by Nate Powell. The music of Otis Redding and Sam & Dave unfurl like plumes of smoke amid the racial turmoil of a segregated Texas town. The lyrics to “Soul Man,” in particular, acquire a rich significance as they are repeated at pivotal moments in the narrative. I’m very interested to see the sounds that will shape Powell’s art in March – a forthcoming comics trilogy co-written by Congressman John Lewis. Harold Cruse’s Stuck Rubber Baby has an abundance of freedom songs and the story’s protagonist, Toland Polk, idolizes the story’s retired jazz vocalist, Anna Dellyne. Although Cruse’s depiction of music is somewhat less evocative that the previous examples, the subtext of haunting songs like Anna’s “Secret in the Air” resonate with Toland’s decision to break his silence about his homosexuality during the 1960s. Likewise, most of the music that appears in Ho Che Anderson’s King is used basically to establish tone and setting, but the song “Sweet Lorraine” from The Nat King Cole Trio stands apart, appearing at the start and finish of the comic to elicit deeper reflection of Martin Luther King’s prophetic role in the Movement.

Most of the songs from this era in American history are celebrated for their capacity to uplift, restore, and persuade on collective registers, but I believe that the comics featured here are most effective in highlighting the introspective qualities of music. The artists and writers go beyond the sounds of “We Shall Overcome,” to transform something as small as the tones of a whistle and as quiet as a photograph into critical instruments of contemplation and mourning. ______________ * The appendix to volume 1 of Bayou notes that Billy’s original name was “Emmet,” but the circumstances of Billy’s death differ slightly from Till’s in the comic which takes place in 1933, not during the 1950s. Comments are closed.

|

AboutAn archive of my online writing on comics, literature, and culture. (Illustration above by Seth!) Categories

All

Archives

July 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed