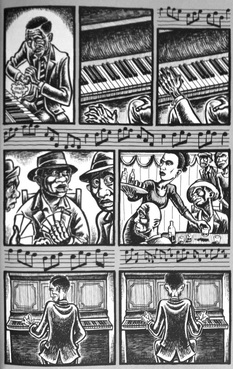

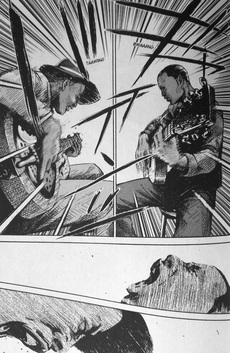

Originally posted at The Hooded Utilitarian. “You heard her, you ain’t blind.” – Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God In the forward to Phillip R. Ratcliffe’s new biography of Mississippi John Hurt the granddaughter of the country blues guitarist describes what it was like to hear Hurt play for the neighbors in the front yard, sitting in his favorite straw back chair with a warm smile and a pan of roasted peanuts nearby. Again and again, she describes the experience in undeniably transcendent terms and insists that it was his “supernatural spirit that had a far greater effect on people than his music alone” (vii). I wonder what Mary Frances Hurt Wright might think of her grandfather’s cameo appearance in the graphic novel, Stagger Lee — whether or not Shepherd Hendrix’s solemn illustration of the bluesman, or the narrative in which Derek McCulloch enfolds him, can convey the mythical power that she once felt as a listener. The lyrics to “Stackolee Blues” are printed above Hurt’s head in a word balloon edged with eighth notes; a crowd stands nearby. The scene, itself, is part of a larger, deeply fascinating blending of history and legend. But when it comes to conveying the quality of the sound that the crowd hears or the magnetic force Hurt’s granddaughter describes, even the most vivid representation can feel inadequate. It is hard to compare the silence of words and pictures on a page to the sound of that first plucked string. Western artists have been enamored with the figure of the black folk musician in public and private moments going back to the nineteenth century. Modern American poets, most notably Langston Hughes, have aspired to an aesthetic in their verse that exemplifies the blues and the social and economic conditions that brought the music into existence. Nevertheless, blues historian Paul Oliver effectively sums up the challenge that awaits any artist or writer influenced by the sounds of Bessie Smith and Muddy Waters: “Blues is for singing. It is not a form of folk song that stands up particularly well when written down” (8). But can a comic fare any better? Does the form’s interplay of verbal and visual elements provide a more dynamic set of tools for representing blues music and culture? My interest here extends to the distinctive ways in which comics approach auditory signification in particular: how do comics sound? Will Eisner, Scott McCloud and others in comics studies often emphasize comics reading as an active, multisensory encounter, guided not only by what’s on the page, but by what is demanded of the reader’s imagination. Which artistic strategies make for a more satisfying experience when it comes to hearing what we see? A blues comic, like any blues narrative, is most compelling when it illuminates the suffering, heartache, and wry absurdity that gives the music its meaning, and exploits the dialogic relationship between the singer and the audience, rather than attempting to replicate chord progressions and flattened notes. To be sure, blues figures run the risk of being caricatured and over-romanticized; their lyrics are often used to invoke African American culture without any meaningful engagement. Noah problematizes this approach quite well in his analysis of Robert Crumb’s 1984 comic biography, “Patton” by pointing out how older blues musicians like Charley Patton are deployed in the story as signifiers of authentic blackness. But blues narratives are just as well known for confronting stereotypes with counter-narratives that resist the easy consumption of the blues as spectacle. (Consider, for instance, how poet Tyehimba Jess imagines the simmering resentment between Lead Belly and folklorist John Lomax.) Comics have their own way of conveying this kind of nuance and dimension, especially when it comes to rendering the intricate rituals of music making. One useful example comes from the three-volume comic series, Bluesman, by writer Rob Vollmar and artist Pablo G. Callejo, published as a single edition in 2008. Bluesman follows two itinerant African American blues musicians from one juke joint to another in the South during the 1920s. Early in the series — which, like the bars of a blues song, is divided into twelve parts — Lem Taylor and Ironwood Malcott persuade a local bartender to hire them by giving the room of drinkers and gamblers an impromptu performance. Callejo’s loose, heavy lines resemble woodcut illustrations that not only help to establish the mood and rural setting, but also to deepen the intensity of Lem’s expression as he sings, eyes closed, and plays the guitar. Musical notes amble through the gutters between panels until the bustling audience falls silent, begins to pay attention, and gradually moves to the dance floor. In Bluesman, sound is generated through carefully accumulated layers of image and text that build from the flutter of Ironwood’s fingers on the piano and Lem’s head thrown back in song to the approving smiles and responsive bodies of the crowd. The lyrics are printed at intervals so that the audience (and the implied readers) can react to what is being heard, as indicated by jagged word balloons containing unattributed phrases like “C’mon now!” and “Oooh, baby!”. The juxtapositions of visual, verbal, and audible impressions easily recall the multi-vocal rhythms of Sterling Brown’s 1932 poem, “Ma Rainey.” But I think the sequential pictures allow us to reflect somewhat more satisfyingly on the elements of performance in such a way that our reading becomes a form of listening. Even if we cannot catch the actual pitch of the notes that Lem and Ironwood are playing, we are certainly more attuned to what James Baldwin describes as the “vanishing evocations” of musical sounds that resonate within. Baldwin, in his short story, “Sonny’s Blues,” also had this to say about musicians: But the man who creates the music is hearing something else, is dealing with the roar rising from the void and imposing order on it as it hits the air. What is evoked in him, then, is of another order, more terrible because it has no words, and triumphant, too, for that same reason. (73) I can think of no better way than this to describe what takes place in the first volume of Akira Hiramoto’s manga series, Me and the Devil Blues: The Unreal Life of Robert Johnson (2008). Hiramoto combines the visual iconography commonly associated with Japanese comics together with a historical rendering of the Mississippi Delta and the supernatural tropes of demonic possession that surround Johnson’s legendary talent with a bottleneck slide guitar. When Johnson (or “RJ” as he is called) begins to play, the black and white panels tilt at long, unsteady angles. The guitar’s head and tuning keys are often positioned in the foreground, forcing our eyes to move up and down the long fingerboard as the strings reverberate. In scenes such as RJ’s stand off with Son House, frenetic background motion lines edge into the blurred contours of the musicians’ bodies and convey the searing intensity of the music. I agree with many reviews of Me and the Devil Blues that the art surpasses the inconsistent narrative, which slips often into caricatures of black southern life. At the same time, the nightmarish premise of the series takes more aesthetic risks that Bluesman and de-emphasizes the collective participation of the listeners in order to transport us into the musician’s psyche. While the audience alternatively delights and recoils at the music being conjured forth, it is the internal workings of Johnson’s spirit that are on display as Hiramoto’s technique forcefully externalizes “the roar rising from the void” — the terrible and triumphant chords that only RJ can hear.

A critical interest in how comics register this supernatural sound need not draw our attention away from larger considerations of black cultural representation and re-appropriation, but more deeply into the social implications of artistic style and practice. Blues is as much a way of seeing in comics as it is for singing. _______ Works Cited Baldwin, James. “Sonny’s Blues” [1957]. Vintage Baldwin. New York: Vintage Books, 2004. Oliver, Paul. “Can’t Even Write: The Blues and Ethnic Literature” MELUS, Vol. 10, No. 1. (Spring, 1983): 7-14. Ratcliffe, Phillip R. Mississippi John Hurt: His Life, His Times, His Blues. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2011. Comments are closed.

|

AboutAn archive of my online writing on comics, literature, and culture. (Illustration above by Seth!) Categories

All

Archives

July 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed