|

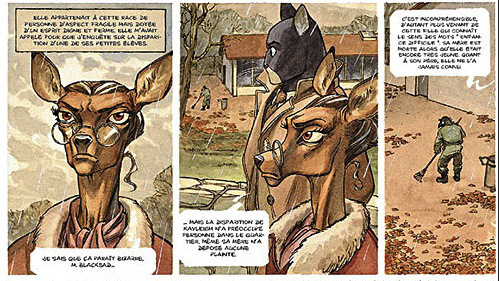

Originally posted at Pencil Panel Page. The Silver Age is often defined by the ways in which comic book superheroes began to develop into increasingly complex figures who managed to right great wrongs in spite of their deep insecurities, imperfections, and strange idiosyncrasies. Some readers characterize them as anti-heroes with ambivalent souls and feet made of clay; others simply describe them as “more human.” Proudly eschewing idealized notions of heroism in the 1960s, Marvel championed the foibles of the Amazing Spider-Man: “the superhero would could be – you!” But talking animals have long occupied the “more human” spaces on the comics page and the question I’d like to pose this week is part of my effort to understand their appeal. Despite the industry’s unshakable association with “funny animal comics” (we have titles like the wildly popular Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories to thank for that), anthropomorphic creatures follow a long tradition of embodying our desires and aspirations whether they originate from myths, folk tales, or children’s cartoons. What’s fascinating to me is the figurative pliancy of animal representations, especially when it comes to heightening the reader’s identification with the characters. As comics readers move from Herriman’s Krazy Kat to Kelly’s Pogo to Crumb’s Fritz the Cat to Speigelman’s Maus, the notion that what we encounter are animals made to act like humans is utterly eclipsed by the troubling realization that these creatures are little more than people who act like “animals.” Pogo put it best: “Yep son, we have met the enemy and he is us.” Last summer, I discovered Blacksad by writer Juan Díaz Canales and artist Juanjo Guarnido. Originally debuting in France and Spain over ten years ago, the hard-boiled detective comic series is now available to English-speaking readers in a translated edition that reprints the first three volumes. (The next translated volume will be released this July!) The extent to which Blacksad ultimately joins the ranks of other well-known anthropomorphic animal comics will be due largely to the way that Guarnido’s award-winning watercolor illustrations bring stunning detail and expressiveness to the brutal crime stories of private investigator John Blacksad, a cigarette-smoking black cat. Clichéd noir devices abound in the series: the trench coats, cocked eyebrows, and murdered Hollywood actresses. But the characters’ temperaments, their glances, even the most subtle bodily movements are shaped by the perceived qualities of their animal counterparts in ways that are incredibly riveting.

Here again, reader identification plays a key role. Scott McCloud argues that we are more inclined to identify closely with illustrations that are more abstract or cartoony. This is certainly the case for a possum like Pogo, but there is something about the precision of Guarnido’s illustrations (and to a lesser degree, Bill Willingham’s Fables) that challenges this claim. Is this because all animals, not matter how conceptually rendered or realistically drawn, always remain abstractions to us? Does the ability to see our mannerisms, thoughts, and ideas reflected in the cruel and wanton acts of the furry intensify our culpability or do talking animals create a safe distance from which to observe the workings of humanity? What kind of critical language serves us best when it comes to interpreting the comic medium’s enduring fascination with animals that talk? Comments are closed.

|

AboutAn archive of my online writing on comics, literature, and culture. (Illustration above by Seth!) Categories

All

Archives

July 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed