|

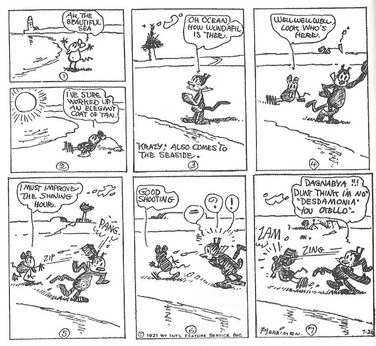

Originally posted at The Hooded Utilitarian. In their essay collection, Thinking about Animals: New Perspectives on Anthropomorphism, editors Lorraine Daston and Gregg Mitman assert that “humans, past and present, hither and yon, think they know how animals think, and they habitually use animals to help them do their own thinking about themselves.” Prompted by the ubiquitous manifestations of anthropomorphism in the arts and sciences, religion and folklore, advertising, and nature documentary filmmaking, the collection’s introduction charts the various psychological, religious, and ethic orientations toward ascribing human behaviors and characteristics to animals and asks: “Has the animal become, like that of the taxidermist’s craft, little more than a human-sculpted object in which the animal’s glass eye merely reflects our own projections?” The question provides us with an opportunity to linger on the cat and mouse game at the center of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat. We might consider what the comic strip’s premise has inherited from Anansi, Aesop, Brer Rabbit, and other tales of talking animals in its serial run from the First World War to the Second, through Women’s Suffrage, the Great Depression, the New Deal, and the Segregation Era. Or we can reflect on how the strengths and weaknesses of Krazy Kat shape our interpretation of animal characters in the comic art and animation that followed Herriman’s lead. Felix, Mickey, Woody, and Fritz come to mind, but anthropomorphic animals as a trope touch a remarkable number of genres and styles, including titles such as Fables, Mouse Guard, Beasts of Burden, Pride of Bagdad, Bayou, Blacksad, and We3. And of course, given the subject of recent conversations on HU, we might even wonder: if it wasn’t for Krazy Kat, would we even have Art Spiegelman’s Maus? While the animals of Coconino County engage a range of social identities and historical contexts against the love triangle between Krazy, Ignatz, and Offisa Pup, I’m particularly interested in the way anthropomorphism externalizes race in the comic strip. Daston and Mitman go on to make the point that animals are not merely “a blank screen” in anthropomorphic representation; their own actions and behaviors as animals bring “added value” to human projections. And so Herriman’s decision to undermine the well-known antagonisms between mice, cats, and dogs is meaningful, and not just because of the way the cartoonist endeavored to conceal his own mixed-race identity. In Krazy Kat, the cat that chases the mouse isn’t driven by food or deadly sport, but by the kind of desire and affinity that is undeterred by species. In order to take part in this desire as readers, we have to accept what Jeet Heer characterizes as “the strange internal logic of the world Herriman created: we never ask why a cat should love a mouse, or a dog love a cat, since it seems natural. And this, perhaps, is where race becomes relevant.” Indeed, the comic strip’s defiance of the “natural order” brings to mind the discredited scientific theories used to superimpose racial categories onto a Great Chain of Being. Herriman’s anthropomorphism may dramatize difference, but not incompatibility and in the process, the comic affirms Krazy as America’s quintessential stray. Heer points out that Krazy’s blackness becomes more pronounced over time, particularly with the appearance of his blues singing “Uncle Tom” cat. Added to this are several comic strips in which racism and white supremacy serve as the primary target of comedic reversals and impersonations. In one story, Ignatz falls for Krazy after the cat has been drenched in whitewash and the mouse longs for the “beautiful nymph” who is “white as a lily, pure as the driven snow.” Once Krazy washes off the paint, Ignatz’s outrage returns. In another instance, Ignatz tans in the sun and throws a brick at a confused Krazy who angrily responds in kind, saying “Dunt think I’m no ‘Desdamonia’ you Otello.” Krazy’s uncharacteristic behavior seems especially odd in this strip until one considers that he is not actually upset because a black mouse has thrown the brick, but because the brick-thrower is someone other than Ignatz. Certainly the Shakespearean allusion speaks to this tragic tangle of racial and gendered constructs. Yet while the racial politics in examples like these are more explicit, I find them to be less compelling and somewhat disconnected from the “strange internal logic of the world Herriman created.” (Having discussed Herriman’s Musical Mose elsewhere, I would argue that this comic strip manipulates the concept of racial and ethnic “impussanation” much more effectively in the way that it sets caricatures against one another.) I believe that it is through the anthropomorphic structures of Krazy Kat and not through buckets of whitewash that Herriman achieves his most complex and multi-dimensional engagement with race and other “human-sculpted” realities. What is your take on how race is shaped by the anthropomorphic tropes in Krazy Kat? Comments are closed.

|

AboutAn archive of my online writing on comics, literature, and culture. (Illustration above by Seth!) Categories

All

Archives

July 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed