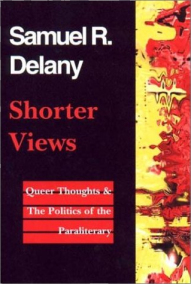

Originally posted at Pencil Panel Page. In an essay that Samuel R. Delany published in 1996 on “The Politics of Paraliterary Criticism,” the science fiction writer closes with a call for comics scholars to abandon the idea of “definitions” and “origins” as a scholarly imperative. Not surprisingly, Delany used Scott McCloud as the catalyst for his argument and while the essay praises much of Understanding Comics, he stridently challenges the premise of the book’s opening chapter in which McCloud settles upon the formulation of comics as “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer.” Critics have since deliberated untiringly over McCloud’s words, but Delany takes issue with the entire definitional project altogether. He characterizes the enterprise as a series of “empty gestures” from the 1930s when “American critics wanted to make literary criticism more scientific” and that ultimately reinforce the false notion that paraliterature genres lack the quality and complexity of literary works (Shorter Views 239-240). Delany advocates a different approach to genre collections such as comics, handling them as “social objects” that are incompatible with rigorous definitions and instead, “exist rather as an unspecified number of recognition codes (functional descriptions, if you will) shared by an unlimited population, in which new and different examples are regularly produced” (239). Many scholars seem to have followed Delany’s lead and left the constraints of definitions behind in the nearly two decades since Understanding Comics was published. Even our little corner of the blogosphere at PPP privileges “functional description” (see posts here, here, here, here and here). “A discipline is defined by its object,” Delany says, “But disciplinary objects themselves are not definable. That’s why they must be so carefully and repeatedly described” (212). If comics scholars are, indeed, moving beyond definitions, then the authority of “origins” may pose our next disciplinary challenge. Among artists, the quest for origins can inspire, but it can also inhibit – or so the reasoning goes: “Because you have not studied the proper origins of the genres, you don’t really know what the genre is (its definition) and so are not qualified to work in it” (245). When critics take up this kind of logic, the results seem to foreclose meaningful inquiry, rather than open it up to fresh insight. The more I learn about the history of American comics – and I still have much to learn – the more unsatisfied I become with the way this knowledge is deployed to confer value and maintain exclusive narratives of influence in modern comics. As Delany cautions, “It is a relation that, in the recognition of similarities, can generate great reading pleasure, richness, and resonance. But it is not a relation in which the earlier work lends force, quality, or some other transcendental authority to the latter” (256).

This claim has become particularly important to me as I cast aside traditional modes of influence to evaluate representations of race and blackness in comics. The “proper” origin stories don’t always work. Resonances can come from all sorts of cultural and historical sources. And sometimes it is not the recognition of similarities, but of differences, that are critically interesting. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with tracing a path from Little Nemo and Krazy Kat to Chris Ware, but I also think that it is useful to keep in mind Delany’s mantra for paraliterary critics: “The ‘origin’ is never an objective reality; it is always a political construct (246). In his essay’s concluding pages, Delany effectively couples the discipline’s attempts at definition with the way we define ourselves as scholars. He writes that, “our discussions are striated by a fear that without the authoritative appeal to origins and definitions as emblems of some fancied critical mastery, our observations and insights will not be welcomed, will not be taken for the celebrational pleasure that they are. What can I say, other than that we need more confidence in the validity of our own enterprise?” (268). How, then, do you read Delany’s approach to paraliterature and the “celebrational pleasures” of criticism? What do we gain (or lose) when we describe the comics we study, rather than arguing over how to define them? Comments are closed.

|

AboutAn archive of my online writing on comics, literature, and culture. (Illustration above by Seth!) Categories

All

Archives

July 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed