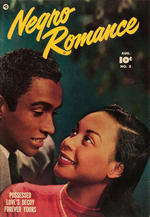

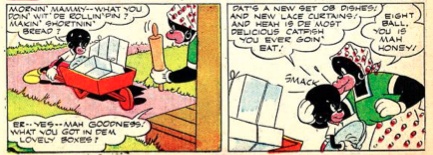

Originally posted at Pencil Panel Page. I’ve spent the first few weeks of my African American Comics class dispelling myths. With a sharp and tremendously engaged group of diverse university students, we’ve tackled questions not just about the form, but also about the range of black representation in America’s earliest comics from Outcault’s The New Bully and Herriman’s Musical Mose to Dell’s New Funnies, Fawcett’s Negro Romance, and EC’sShock SuspenStories. This week I asked the class what surprised them most about our readings so far and a few voiced their initial skepticism that a course on black comics could have enough material to last a full semester. (One student is particularly pleased that she can argue now about comics with friends whose experiences begin and end with Batman.) So far the Negro Romance story, “Possessed” and the first issue of Rural Home’s Jun-Gal have inspired the liveliest exchange. But what has stuck with me is the conversation surrounding our analysis of a Li’l Eight Ball story from a December 1945 issue of New Funnies. The story is very much in keeping with the slapstick humor of other Walter Lantz characters. A clumsy little boy tries to please his mother in a simple plot that revolves around physical comedy and a serendipitous happy ending. Still, the boy in this story has a large shiny pitch black head, oversized pink lips, and wears white gloves. His plump “mammy” wears an apron and handkerchief around her head as she scolds her son’s well-intentioned antics. Immediately the students targeted the physical features of the characters; we referenced blackface minstrels and the game of pool, juxtaposed Eight Ball’s quasi-human features with the story’s animals, and remarked upon the dialect that clearly marked him racially and regionally. We compared the images to other problematic black caricatures from earlier comics that we had studied.

The room got quiet then and something much more interesting happened. One student raised his hand and admitted that he still liked it, thought it was quite funny when he first read it. Another agreed. Then another. (This was a first for me.) Some were on the fence, puzzled by their own reactions. A couple thought the title character seemedstrangely familiar. Other students continued to insist that the offensiveness of Li’l Eight Ball was undeniable and that no black people, either in 1945 or 2013 could find it funny. Except that there were several readers (black and white) in my class who did. I ended the class by sharing unattributed details from Don Markstein’s Toonopedia that the title’s editor may have pulled Li’l Eight Ball in response to written protests from a group of black schoolchildren. This effectively ended our conversation for the day, but I have felt since then that there is much more to say about the collective tensions reflected in the students’ conversation. Certainly we can intellectualize our first encounter with this charged material, distance ourselves from both the pain and pleasure of the reading experience for 1940s consumers. Being honest about our own reactions involves a different kind of risk, one that I’m quite proud of my students for taking. How do we process controversial comics that are designed to “entertain” and draw on formulas traditionally associated with light-hearted amusement, but that also bear the legacy of painful racial misrepresentation? Is it okay to laugh at Li’l Eight Ball in 2013? Comments are closed.

|

AboutAn archive of my online writing on comics, literature, and culture. (Illustration above by Seth!) Categories

All

Archives

July 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed