|

Originally posted at Pencil Panel Page. I don’t give much thought to page numbers when I’m reading comics simply for pleasure, but in my research and teaching, their absence can be exasperating. I can’t remember how many times I counted the 300+ pages in volumes 1 and 2 of Jeremy Love’s Bayou for an essay that I published on the series, and in the end, I don’t know how helpful my citations are for those who don’t take the time to count out each page on their own. And any instructor who has ever taught Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth knows what a bizarre experience it is to refer to Chris Ware’s pages in purely descriptive terms or in proximity to the narrative’s tiny paper cut-outs while the students flip madly through the book to catch up. The origin of this practice may be related to the history behind comics editing and printing procedures, particularly given the insertion of ads and other extra-textual material in the traditional comic book pamphlet format. In his cultural history of the medium, Comic Book Nation, Bradford Wright didn’t even bother to include page numbers in his citations, claiming that “pagination in comic books is inconsistent and generally irrelevant” (xix). Writer Derek McCulloch has experienced this inconsistency first hand. For his work at Image Comics, he explains: “I’ve had final say (along with the artist) over virtually every aspect of what’s on the page, I made sure that there were page numbers onStagger Lee and clean forgot to ask for them onPug.” But his experience has been quite different at DC Comics, where he had little say over the production process. His latest graphic novel with artist Colleen Doran, Gone to Amerikay, a story that combines history and mythology to explore three generations of Irish immigration to America, doesn’t have a single page number.

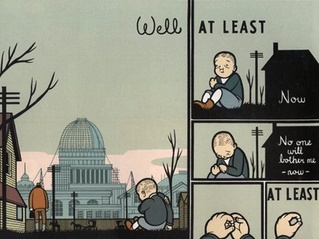

Artist Eric Battle has had similar experiences working for Dark Horse, Marvel, and DC Comics, but he notes that with independent presses and creator-owned projects that “if pagination is intrinsic to the overall page design and I outline the specific need to have the pages numbered, I can’t think of any reason for the idea to be vetoed.” I have to admit that I hadn’t considered pagination as an element of “page design” or “need” before, only the ostensibly self-evident utilitarian uses. So the inconsistency to which Bradford Wright refers is pretty evident then, but the question of relevancy is another matter. Are page numbers irrelevant in comics? The design of older serial comics may have been more heavily influenced by printing restrictions, but the decision regarding whether or not to number pages in today’s comics and graphic novels seems oddly impractical and yet, potentially laden with rich aesthetic implications. In the case of Jimmy Corrigan, for instance, I’m struck by the ways in which Ware sets us adrift in the diagrammatic images that shift back and forth through time; missing page numbers seem to heighten this sense of narrative unmooring. In another instance, Hillary Chute has remarked that Art Spiegelman’s unorthodox page numbering methods for In the Shadow of No Towers demonstrates “a material register of trauma’s inability to conform to the logic of linear and temporal progression” (Chute, qtd in The Jewish Graphic Novel). So how does pagination shape the way you read comics? Might the use of page numbers enhance or detract from the storytelling process, or does the inconsistency simply exacerbate the perception of comics as disposable reading? I wonder, too, if pagination reflects how readers and creators approach comics predominately as objects of visual or verbal art? Special thanks to Derek McCulloch and Eric Battle for their help with this post! Comments are closed.

|

AboutAn archive of my online writing on comics, literature, and culture. (Illustration above by Seth!) Categories

All

Archives

July 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed